We have all heard those developer statements of map size in open world games nowadays. They can often based on comparisons “several times larger than game” or similes “as big as”. I used to get excited by these announcements. This was until the actual games came out and more instances of this occurred. It is now apparent that size is no longer a major factor for a sandbox. The important factors are the ones that value density and other quality-checking sections, determining whether a sandbox is filled with the gaming equivalent of sand — substance.

A Brief Mention of Landmark Open World Games

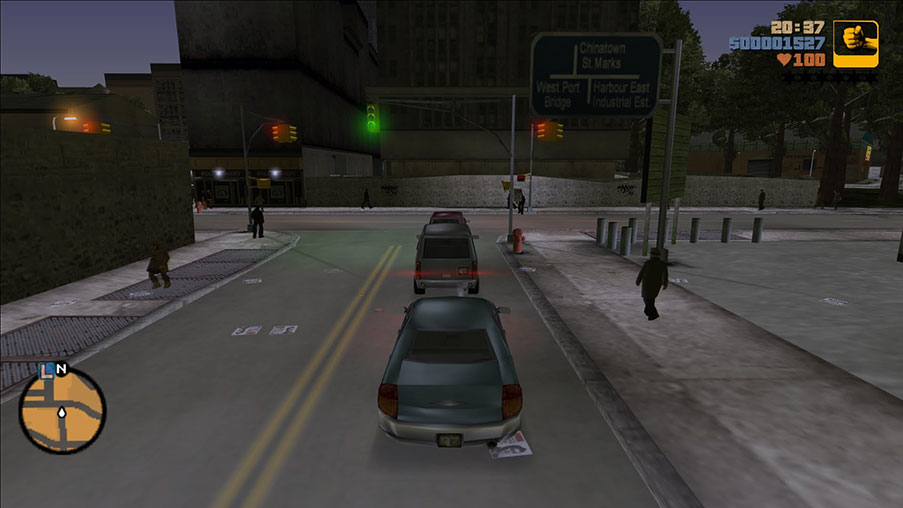

Way back when open world gaming was starting to become prevalent, benchmarks were very few and far between. The sole concept of being able to explore a virtual world at your own pace was an superbly solid opportunity for gamers at the time. They did not really care for the objective side of these games but rather the newly emerged ability to free-roam. Early games in the 3d rendition of the genre such as 2001’s GTA III and its subsequent clones were limited in features. Collectables and other staples of the genre were not implemented because these games were trying to establish a foundation. GTA 3 focused on exploration and open world design more than anything else. Its relatively large Liberty City was more-than-enough to entice players, not to mention a revolutionary mission format.

A year later, The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind was released. Alongside World of Warcraft in 2004, these 2 titles opened up many opportunities in open world gaming. Quests, massively generated worlds, and so on. These perfect mixes of RPG elements with the new genre took the gaming world by storm. Soon, most subsequent releases within the genre would take cues from these games as well as the essential design of GTA III.

The Scourge: Collectables

After these pioneering titles of the genre showed what could be done, modern technology needed to step up. In the seventh generation (2005-2013), the new technological power provided by Xbox 360 and PS3 gave a near-limitless amount of opportunities for open world gaming. In turn, gamers graced with expertly crafted worlds seen in titles such as Red Dead Redemption, Skyrim, Assassin’s Creed 2 and GTA IV/V. But with most major open world games hitting the mark, some wrought bad staples to come. Assassin’s Creed 2 and GTA IV’s feather collecting and pigeon killing, respectively, laid the groundwork for a degradation of the genre. Collectables.

Collectables is one of the titular scourge. They merely serve as a seemingly outstretched hobby of collecting the same scattered item. What is most insulting is that collectables are one of the key reasons to explore an open world nowadays. It seems like some developers will focus more and more of their time filling their maps and justify it as furthering play time. What it is an easy way of padding a game and the medium should be able to provide a greater reason to explore. And when there is more collectables, the map is bigger.

The Scourge: Focus on Size

There is an unhealthy demand for size in these games. As a result, the actual content in these games has regressed. Activities are less meaningful as well as overall immersion. What distinguishes video games from other media is that they are very interactive. Open worlds should embody this more than any other genre. But yet, huge but inconsequential spaces surround the player. There is a fine line between world design, concept, and interactivity. The ideal open world should look beautiful, is conceptually original, and immersive.

Those desirable qualities mentioned can come into one another in harmony. This harmony is ultimately determined by how a gaming world will fit with the gameplay. Something like Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, while being set in a barren Afghan desert, is striking in its own way and fits into what the game is about. It does not have much in the way of interactivity but is forgivable in the way that it gives players different opportunities for stealth. And while it may not be dynamic in ways of NPCs and events, the weather system makes the world seem alive and provides more possibilities. Phantom Pain also has its fair share of side quests and icons but not in a way that is superfluous.

Some games can solely focus on the size, though. Similar to the aim of Phantom Pain, the stealthy military simulator ARMA III puts players into Greece and the map is many times larger (104mi2). On the other hand, the gameplay is nowhere near as well-implemented as Phantom Pain’s and what little campaign seems scripted. Sure, freedom of playing aggressively or sneakily is still prevalent but it starts feeling very bland and lifeless.

How the Genre Should Evolve

There also some games that will focus mostly on the to-do list side. The biggest offender is one of the collectable firestarters — Ubisoft, the developers/publishers behind Assassin’s Creed & Watch Dogs. These two open world franchises have beautifully realized that does not border on lifelessness while also being big. However, the incentive to explore these worlds are hampered by the activities. Many are tedious side goals that do not offer much to the story as well as endless collectables. Assassin’s Creed’s historical locations should be immersive enough to not encourage collecting to explore.

Virtual sandboxes should be filled with wonder and surprises. If not, they should exist to serve the gameplay well and provide the player with a sense of freedom & even choice. The gaming community is not asking for an infinitely procedural world (I am looking at you No Man’s Sky). What gamers want is an open world game with characters and activities akin to hub/zone games. These types of games do not have big maps but value quality over quantity by varying environmental design. There is also an emphasis on NPC and world interaction. Games such as Deus Ex, the Persona series and, to an extent, Dragon Age series are good examples.

In conclusion, what the open world developers should think of is the value of quality over quantity. All of these promises of size sound good on paper, but the world is only as good as it is executed. Is it tonally suitable? Does it serve the story? Will there be a consequence on gameplay? But most of all, will exploring the world be an engaging and immersive experience? Once developers get past the checklists, collectables and empty space will the genre fully flourish.